Finding William and Sarah Ramsey

[This article is reprinted from my Ramsey-Farrell Family History Newsletter of November, 2003. A recent trip to Kennesaw Mountain has motivated me to post this article in the blog. In any case, future such articles will almost surely be posted here, rather than printed as a hardcopy newsletter. We've actually made a little further progress iin learning about William and Sarah Ramsey, but I'll tell you about that separately when we have it sorted out a bit more.]

A Good Day in the Life of a Genealogist

In the early 1990s, I had a professional conference in Atlanta, Georgia. For many years, I had hoped to find an opportunity to go there, because my G-Grandfather John Cannon Ramsey was born there. This was before the days of genealogy on the internet, and it seemed that my best way of finding his (then unknown) parents was to actually go and do research there in Atlanta.

John Cannon Ramsey

I was aware of an interesting family tradition about John Cannon Ramsey’s name. He is said to have been born in Atlanta during the siege of Atlanta, as Sherman did his famous march to the sea, destroying Confederate installations (and much else) that lay in his path. During his birth, the Ramseys could hear Sherman’s cannon fire in the distance, and so they named their son “John Cannon”. The problem with this story was that Sherman’s siege of Atlanta took place a month after the birth date I had for John Cannon Ramsey, and I always wondered if this story was one of those family myths, a nice story that would prove false in the end. Or, more likely, I had an incorrect birth date.

My conference ended on Friday, and the vital records office was closed until Monday, so I spent the weekend in the public library genealogy department. I probably spent 12-15 hours there, and didn’t find a thing. Once, when I was bored, I got up and walked around. I spotted a huge book on top of a filing cabinet, and looked to see what it was. It was a book of Civil War maps. I turned to the map of the siege of Atlanta. One thing that interested me was that Sherman’s march, which I’ve always thought of as a “blitzkrieg”, was quite a bit slower than I expected. Otherwise, I didn’t learn much from the map, either.

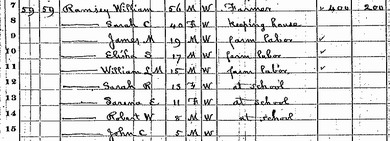

I had two days available to work at the vital records department, and I searched diligently through the records for Atlanta and the surrounding territory for our ancestors. With about two hours remaining, it was clearly time to try a new approach. I thought of the map, and realized for the first time that I might have the date (and the story) right, and the place wrong. I looked where Sherman was the month before Atlanta, and found them within a few minutes. They were some 35 miles north of Atlanta (blitzkriegs were slower in those days ![]() ), in the Wildcat District of Cherokee County, Georgia. Here’s their 1870 census record (I also found them there in 1860).

), in the Wildcat District of Cherokee County, Georgia. Here’s their 1870 census record (I also found them there in 1860).

In addition to William and Sarah C. Brown Ramsey, you can see James Manley (“Manley”), Elisha S. (“Lish”), William Lawrence, Sarah Ruth, Sarena Elizabeth (“Betty”), Robert Wylie (“Wylie”), and our John Cannon.

The 1860 and 1870 census records here are the earliest traces I’ve found of our Ramseys [no longer true], but I’m still looking. William was born in North Carolina, and Sarah C. Brown was born in North Carolina or possibly South Carolina. I haven’t found further records of them in any of these places yet. There’s one more hint that will help, and I’ll discuss it below, but first let’s talk about cannons.

So What About the Cannons?

Here’s a segment of a wonderful map showing Sherman’s path through northern Georgia. I’ve highlighted Cherokee County, and marked the Wildcat District. I hope to use land records, or details of the census records, to locate the Ramseys more exactly, but haven’t been able to do this yet [this is also no longer true; we've found the land records, and the family farm was right at the south edge of the Wildcat District].

(Used with the kind permission of David Mastovich;

original larger map is here)

Although Sherman burned about half the town of Canton in response to a series of guerilla raids, there were no actual battles in Cherokee County. It seems highly likely that the cannon fire was associated with the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain, which stretched over the last half of June, and took place about 11 miles south of the Wildcat District. A three-day-long artillery barrage took place 19-21 June, 1864, and the fiercest fighting and largest artillery barrage, took place on 27 June 1864. I’m betting that if we ever learn John Cannon’s actual birthday, he’ll have been born on one of those four days. It’s interesting that his birth month brought us (correctly) to the place he was born, and the events that occurred in that place now suggest when he might have been born.

The Battle of Kennesaw Mountain

An army travels on its stomach, and Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman‘s greatest challenge as he invaded the southlands was to maintain an open supply route. His strategy was to follow the path of the Western & Atlantic railroad from Chattanooga down through Atlanta, rebuilding and defending the railway behind him. Keeping the railroad working all the way to his supply base at Louisville would be ideal, but he had also established huge storage facilities at Nashville, which might suffice in a pinch. Naturally, the Confederates were interested in preventing him from advancing on the rail route, and they would destroy the railroad both ahead of him and behind him to the extent they were able to do so.

Gen. Joseph E. Johnston‘s Confederate forces were outnumbered two to one, and couldn’t afford a pitched battle in neutral terrain. Trickery wasn’t working for them, either. Johnston’s neat trap at Cassville was foiled when a small group of lost Union cavalry happened to spot them, and sounded the alarm. And Sherman’s intimate knowledge of northern Georgia allowed him to sidestep an ambush at Altoona Pass. And for the rest of the six weeks since the start of the Atlanta Campaign, Sherman’s flanking maneuvers had forced Johnston to gradually retreat eighty of the hundred miles’ distance down the railroad from Chatanooga to Atlanta. Even Johnston’s defensive victories at New Hope Church and Pickett’s Mill had been more costly, percentagewise, to the Confederates than to the Union forces.

But with the retreat to Kennesaw Mountain on June 15, 1864, Johnston finally found himself in a truly defensible position. Standing to a height of 700 feet and more than two miles long, the twin peaks of Kennesaw provided substantial natural fortification, and lots of opportunity for man-made trenches, entanglements, and sharpshooter positions. The side facing the Union forces is steep and rocky, while more gentle slopes on the southeast side allowed ready access for the rebel forces. Swollen creeks had created swampland just in front of both ends of the 6-mile arc of defensive entrenchments built by the Confederates, providing protection against a flanking attack. With the railroad running just past its east end, Kennesaw Mountain was a perfect defensive position. It seemed impregnable.

As a preparatory step while reconnoitering the position, Sherman launched an artillery barrage on the fortifications of the mountain. This barrage involved 130 cannon, and continued nonstop for three days, on June 19, 20, and 21. Sherman, his troops said, was determined to either take the mountain or “fill it full of old iron”. This certainly could be the cannon fire that our Ramseys heard, though there was an even greater barrage later, as we’ll see.

Sherman side-stepped his entire army to the right, and his generals Hooker and Schofield advanced their forces in a flanking attempt. Johnston had prepared for this possibility by moving Gen. Hood’s Army Corps from the right end to the left end. The ever-aggressive Hood attacked the entrenched Union forces at Kolb’s Farm, but couldn’t break through, and lost 1000 men to Sherman’s 350. In failing to pursue, however, the northerners gave Hood’s forces time to set up their own entrenchments. That effectively stopped further flanking attempts by Sherman, unless he was willing to over-stretch his forces and leave his supply line quite vulnerable.

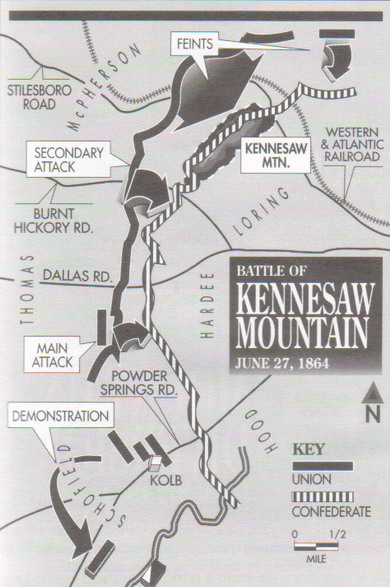

Map of the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain (reprinted from Dennis Kelly’s excellent book, “Kennesaw Mountain and the Atlanta Campaign: A Tour Guide”, with permission; full reference below)

Sherman now found himself considering the reverse of his usual flanking attacks. He felt that by holding on the flanks and attacking the obviously-strong center, he might achieve sufficient surprise to succeed, and might in any case correct a laxness that was beginning to set in with his own troops after six weeks of flanking and feinting with relatively little serious fighting. He gave his field commanders two days to prepare, while withholding knowledge of the battle plan even from their own staffs.

On June 26, the day before the planned battle, Schofield’s troops at the south end of the eight-mile-long front demonstrated loudly, and feigned preparations for an attack, hoping to induce Johnston to move troops there and weaken his center. He didn’t take the bait.

For 15 minutes, starting at 8:00 AM, June 27, 1864, the whole of the Union army’s artillery (some 250 cannons) laid down a barrage, especially on Big Kennesaw and Little Kennesaw and the little spur now called Pigeon Hill at the south end of the mountain.

The print above (Louis Prang, 1880s) shows a part of the huge artillery barrage Sherman laid down against the Confederate forces holding Kennesaw Mountain on the morning of June 27, 1864. (Modern reprints of this image can be obtained here.)

When the cannon fire stopped at 8:15, Union forces launched a feint attack on Big Kennesaw (the eastern end of Kennesaw Mountain, by the railroad) and two seriously intended attacks at Pigeon Hill and at Cheatham Hill, farther to the south. These attacks incurred heavy Union losses (Sherman estimated 3000), while doing little damage to the enemy, and without dislodging the Confederates. The battle was clearly a victory for Johnston.

But ironically, Johnston and his commanders were sufficiently distracted by the heavy Union assault that they failed to pay adequate attention to Schofield’s feigned attack at the south end of the battle front. There, Gen. Jacob D. Cox alertly and skillfully took advantage of the situation, and made inroads into the Confederate defenses that were to provide the basis for Sherman’s next move, another flanking movement to the south end of the line. This forced Johnston to abandon his position on Kennesaw Mountain on July 2, and retreat several more miles toward Atlanta.

Our little history is now so close to a critical turning point in the war that I think I’ll go ahead and tell the story, even though it has nothing directly to do with Kennesaw Mountain or the Ramseys. Johnston was a very skillful strategist whose ability to delay Sherman for eight weeks while gradually conducting an orderly retreat to Atlanta was a significant success. Atlanta really was impregnable. By mid-July, Johnston was in Atlanta, surrounded by the now badly stretched-out forces of Sherman. On the eastern front, Lee was barricaded into a similar fortress at Petersburg, with the result that the entire Civil War was in a stalemate. If the South had been able to maintain this situation until the coming federal presidential election, it’s likely that Lincoln would have lost the presidency to a concession-minded candidate. Had that happened, the United States would not now exist. Only a miracle could prevent this.

The miracle came when Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederacy, stupidly removed Joseph Johnston from command, and promoted Hood in his place. Hood immediately started attacking everything in sight. Indeed, his tendency to attack at every opportunity converted a defensible position to an eventual loss, and Sherman held Atlanta, and effectively Georgia, by September 2. This so raised northern spirits that Lincoln won re-election in a landslide, and continued the war to the end.

The Ramsey Family Plot at Marysville

But it’s time to return to family history. It’s easy enough to work forward in the Ramsey family. Between 1870 and 1880, they moved to Cooke Co., Texas, where they lived in Marysville. But working backward in time has proven difficult. Both William and Sarah have relatively common names, and it’s hard to trace them without knowing anything further about their birthdates, birthplaces, date or place of marriage, etc.

The situation changed earlier this year, though. While searching the internet for more information about William and Sarah, I came across a tombstone survey of the Marysville Cemetery. There they were, although there was some confusing information. Sarah was listed twice, with conflicting information — a vestige of an old DAR survey, as it turns out. I sent an e-mail message to Barbara Jarvis to thank her for the survey and ask about the discrepancy. Since she indicated on the website that they were going to resurvey this cemetery sometime later in the year, I said I hoped they would take photos of the Ramsey graves, as they had done for some of the other graves there.

The next day, she and her husband went out to the cemetery, took seven photos of the Ramsey plot there and sent them to me. They also resolved the discrepancy. The plot is a fenced-in area with several graves, including William and Sarah, their children William Lawrence, Sarah Ruth, and Sarena Elizabeth, as well as Sarah Ruth’s husband, W.A. Whittington.

The most exciting thing, though, was the amount of detail on the tombstone of William and Sarah. As you can see below, it shows birth and death dates for both, as well as their marriage date. It’s a rare tombstone that contains this much historical information.

Although I still haven’t found them before the 1860 census in Cherokee County, Georgia, we’re now armed with information that should help us recognize them when we do. There’s a lot that I haven’t done yet to try to find them, and I’m now hopeful indeed. I’ll keep you posted. Maybe we’ll even get lucky and one of the readers of this newsletter will have information that will help. ![]()

Sources for More Information

For more information about the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain:

- The Chronology of the Atlanta Campaign

- North Georgia History

- Georgia in the Civil War (Darin Briskman)

- The Battle of Kennesaw Mountain (Randy Golden)

- Dennis Kelley, “Kennesaw Mountain and the Atlanta Campaign: A Tour Guide”, Kennesaw Mountain Historical Association, May 1990. (ISBN: 0962696005) (can be ordered by phone from KMHA)

- Shelby Foote, “The Civil War, A Narrative: Red River to Appomattox”, New York: Vintage Books, 1974 (ISBN: 0394746228; excellent coverage of the Atlanta campaign, pp. 318-424; Kennesaw Mountain 391-402).

- Maps of Georgia During the Civil War

For Cherokee County, Georgia:

- Cherokee County, Georgia Genealogy

- Rootsweb, Cherokee Co., Georgia

- USGenWeb Archives, Cherokee Co., Georgia

- Cyndi’s List, Cherokee Co., Georgia

- Historical Atlas, Cherokee County, Georgia

- Map, Cherokee County, Georgia, 1864

- Cherokee County Historical Society

- Northwest Georgia Historical and Genealogical Society

- Rev. Lloyd G. Marlin, “The History of Cherokee County”. Atlanta: Walter W. Brown, 1932 (1997 reprint can be obtained from CCHS, above)

For Cooke County, Texas:

- Cooke Co., Texas Cemeteries

- Cooke Co., Texas Genealogy

- USGenWeb Archives, Cooke Co., Texas

- Cyndi’s List, Cooke Co., Texas